I’m loathe to give a single penny to tax prep software because some significant percentage of money they take in gets redistributed in a lobbying effort to make sure that Congress keeps our tax code complicated and does absolutely nothing to simplify tax preparation for Americans.

But I’m way too lazy to actually prepare my taxes by hand. That’s fairly complicated, error-prone and annoying. Normally I pick the cheapest tax prep software I can find. This year and last year, that meant OLT (OnLine Taxes). The cheaper software works fine, but the biggest limitation is that it won’t import forms like W2s or 1099s from stock sales. Because a substantial portion of my income is from stock grants by my Employer, there’s a tedious amount of information to enter, there. OLT will let you create a spreadsheet of their own proprietary design and import it. Normally, this isn’t any less tedious than just entering the data in the web form, but this year I realized AI could do this for me.

Claude is my current favorite, so I uploaded my 1099-B, the instructions from OLT for a custom spreadsheet and waited a couple of minutes for it to tell me the spreadsheet was ready to upload. It imported perfectly, but then I had some follow up questions for Claude about disqualifying wash sales when it occurred to me that I was doing this all wrong.

I created a new directory on my file system, dumped all of my tax documents into the directory and fired up Claude Code. I told it that it was going to be filing my taxes for me using the documents I gave it access to, and told it to find the relevant forms and instructions on irs.gov.

It did. It asked me a few questions it didn’t know the answer to, “Do you have any kids?” and then proceeded to prepare my taxes flawlessly in under minutes. It produced a dozen text files, each one a line-by-line representation of the IRS forms and what I should put in what form.

Now that we’d come this far, it seemed silly to copy/paste from text files by hand. I started to ask Claude to fill out the IRS pdfs, but it was struggling with this, and furthermore, it meant I’d need to file by mail. The IRS will let you e-file without tax prep software if you fill out your tax forms on a pretty terrible website. Claude has a Chrome browser extension that will let it use your browser with you. So I signed up for an IRS account and pointed Claude at the empty 1040.

I pretty quickly ran into the usage limits for my $20/month Claude Pro subscription. Fortunately, Anthropic had sent us $50 in “extra” tokens to use for free as part of the Opus 4.6 announcement. I activated those tokens and let it go.

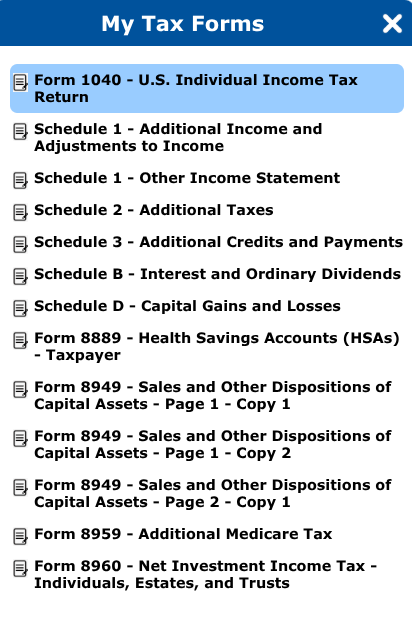

And go it did. It filled out not just the 1040, but all the schedules and worksheets necessary.

It was incredibly slow and ponderous at this. The website is poorly designed even for humans, and terribly designed for robots. It had to constantly take a screenshot and calculate where to click the mouse to enter the next thing. It took it about 2 hours, but it succeeded!

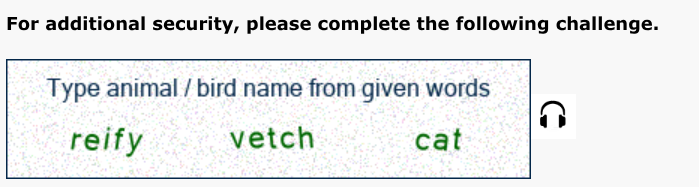

For sanity, I double checked the totals with OnLine Taxes and they lined up. I went ahead and e-filed, without giving the tax prep industry a penny. The IRS probably needs to rethink this check to see if the form is being filled out by a robot:

In June of 2025, Dwarkesh said:

When I interviewed Anthropic researchers Sholto Douglas and Trenton Bricken on my podcast, they said that they expect reliable computer use agents by the end of next year. We already have computer use agents right now, but they’re pretty bad. They’re imagining something quite different. Their forecast is that by the end of next year, you should be able to tell an AI, “Go do my taxes.” And it goes through your email, Amazon orders, and Slack messages, emails back and forth with everyone you need invoices from, compiles all your receipts, decides which are business expenses, asks for your approval on the edge cases, and then submits Form 1040 to the IRS.

I’m skeptical.

I was skeptical, too. Obviously, this wasn’t quite the task, but it wasn’t that far off from the task. I’m a lot less skeptical, now.